E1027 On a scale from 1 to 10, about how forgotten have you been in the history of architecture? – Ilinca Pop

«There is a cliche in everything. That’s how the truth comes in.» Nadia de Vries, «Now That I Am a Cursed

«There is a cliche in everything. That’s how the truth comes in.»

Nadia de Vries, «Now That I Am a Cursed Woman», from «Dark Hour»

«Fairy tale house» – another kind of house?

As I was asking myself what attitude we should have while talking about «the fairy tale house» so as not to unleash the middle class cliché, I stopped at the thought that it became an expression almost impossible to use in an honest text about architecture. Next to «the dream house», it belongs more to the pile of expressions used in the sales department: «holiday in a fairy tale house», «buy your fairy tale apartment» and so on, by the same token with the meta-metaphor used by the dairy producers: «yoghurt from once upon a time» that Vintilă Mihăilescu (1) talks about. Obviously – and it might seem pedantic of me – some personal predispositions will make the notion «fairy tale house» to have real meaning for some and mean less to others; of course, any house can be a fairy tale house. Beyond this thought, of course, the events around the houses and inside the houses become the stories of the houses themselves, because architecture is first understood through use (2). Therefore I will continue to speak about the story of a house, villa E1027, Eileen Gray’s project from Roqueburne-Cap-Martin, in the South of France.

E1027 – A starting point

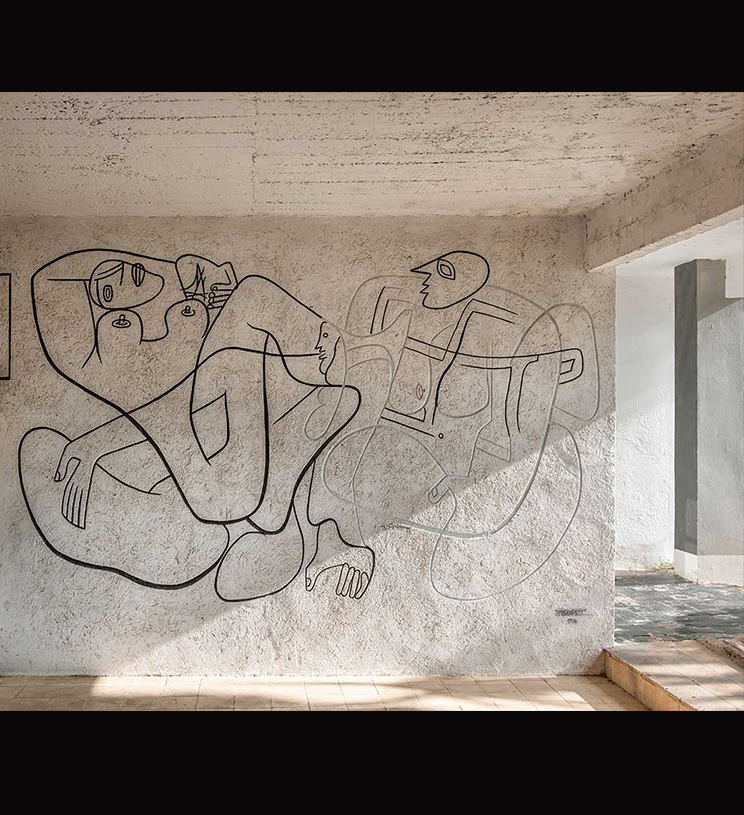

The story of the E1027 villa is surrounded by the intellectual conflict between the project’s author, Eileen Gray and an ardent admirer of the villa, Le Corbusier. The scandal aura is ensured by the famous photographs with Le Corbusier, naked, painting on one of the walls of the E1027 villa. Although they don’t always make for a spectacular role, or even the object of a more complex psychoanalysis, we will find out that Jean Badovici, the villa’s owner, was actually very pleased by the entire «mise en scene» of the paintings.

The E1027 takes over all the main language elements of modern architecture from the 1920s, while also expressing a special sensitivity through its details – «the house as a living organism», where there is an «atmosphere fit to host interior life» (3). Eileen Gray designs the project starting from the interior and working her way out to the exterior. She works with a series of lighting studies while imagining the space of the villa with astute detail: from structure to object. On top of lending her attention to all the furniture pieces – that in their turn are an integrant part of the project – she also gives special attention to the surroundings – she uses a series of adjustable shutters to protect the sunny areas from excessive light and wind. Some of the objects Eileen Gray designs for E 1027 reflect the special consideration she gives to the senses. Amongst these objects we name the tea trolley, covered in cork to soften the noise made by tea cups (4).

«The living room opens onto a terrace, from which it is divided by a range of sliding- folding windows; these open out against two column. The terrace is further screened from the outside by a set of engulfing awnings which shelter it against the southern and western sun. […] Correspondingly, anyone inside the main living room knows himself to be separated from the outside world by an intermediate zone. […] With this all, an enormous care has been taken over the surfaces […] the main ceilings are not plastered, but are in painted exposed concrete, the roof slab being suspended from the beams so as to avoid the unpleasant details at the joint of wall and ceiling, and the cracked ceiling plaster.» (5)

Beyond the articles on the villa per se that leave aside, and are right to do so, Le Corbusier’s murals, there are a few lines of speech (that partially overlap) that have exposed the story of this house: the theoretical-feminist perspective, the psychoanalytic-conservatory, the speculative-incriminatory and the academic-biased. Behind what now seems to be a reading exercise (or an experiment on synthesis) there is some discontent that from my point of view is deepened by the historical context of events – mid 20th century. Although Eileen Gray finishes building the villa in 1929 (when Le Corbusier is still working on Villa Savoye and Mies van der Rohe is inaugurating the Barcelona Pavilion), her villa comes to the attention of the public only in the last few years, after its opening within the UNESCO site at Cap-Martin.

E1027 – Investigative perspective

In 1923, Le Corbusier published «Vers une Architecture» where he was presenting the now well-known five points of modern architecture: building on «pilotis», roof gardens, free designing of the ground plan, horizontal window, free design of the façade. The ideas were already on the move in the articles he published in «L’Esprit Nuveau» between 1920 and 1925, but they were not necessarily familiar to the large public. The famous Villa Savoye was to be finished in 1931. Around 1922, Eileen Gray, an architect of Irish origin living in Paris, asked her friend, Evie Hone, (6) for copies of L’Esprit Nuveau and thus met in her readings what was to become «une architecture». At the time, Eileen Gray hadn’t designed any individual houses, as her work was focusing more on object design and art deco furniture, works that had been exhibited repeatedly in Salon D’Automne between 1922 and 1923.

In 1926, the friendship between Eileen Gray and Jean Badovici, the editor of «L’Architecture Vivante», made possible the realization of the architect’s first project: E1027, a holiday home for Badovici, in Southern France, at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin. Strongly sophisticated and very minute in her architecture and its details, Eilleen Gray awakes Le Corbusier’s admiration who, knowing Jean Badovich, visits the villa after 1930 and spends the holidays with «Badou». Later, in 1938, the owner of the villa asks his good friend, Le Corbusier, to intervene on it with a series of mural paintings, without the architect’s blessing or knowledge. The photographs depicting Le Corbusier naked and painting the exterior walls of the Villa E1027 stand as proof, together with the actual murals, now protected. Even later, in 1951, after Badovici’s death and after Le Corbusier’s failed attempt to buy E1027 for himself, he builds a little holiday refuge (The Cabanon) close to Eileen Gray’s villa. The decision comes after a longer period when, due to some time spent on some construction sites led close by, Le Corbusier had built a friendship with Monsieur Rebutano, the owner of Etoile du Mer, the bistro, where the architect would dine together with his team – habit he kept even after the construction was finished. In 1965, the architect drowns in the waters in front of the Villa E1027. Rebutano’s son and the heir of the bistro becomes one of the initiators of the touristic project around Villa 1027 and the Cabanon, area now protected by UNESCO.

E1027 – The Manifest Perspective

Eileen Gray (Kathleen Eileen Moray Smith) was born on the 9th of August 1878 in a noble Irish family. She studied at Slade School, in London, and then at the Académie Colarossi and Académie Julian, in Paris. She worked with Seizo Sugawara, in his studio in Paris. She was so passionate about her work that she suffered health problems from vapour intoxication from the paint she used for the furniture. Starting with 1912 she received more complex commissions: interior design projects for rich families. Villa E1027 was the first dwelling thought to the last detail by Eileen Gray, a vacation home for a close friend: the editor of «L’Architecture Vivante», Jean Badovici. Through a personal interpretation of modernism, Gray brings to light at Cap-Martin an entirely sensitive architecture which is at the same time very thorough. Nevertheless, her architecture is rapidly overlooked in literature and other publications where even her name is misspelled repeatedly: «Helen Gray» (Le Corbusier, «My Work», 1960), «Eillen Gray» (Badovici, 1924), «Eleen Gray» (Vauxcelles, 1920–1923), «Ellen Gray» (Waldemar George, 1920–1924), «Eelen Gray» («Des Canons, des munitions?») (7).

The friendship between Badovici and le Corbusier facilitated – because Badovici was the owner of the villa – the addition of some mural paintings made by Le Corbusier between 1938 and 1939, without the architect’s blessing. Part of the paintings was made through enlarging drawings with the help of an image projector (8). Although Gray did not appreciate this intervention at all, calling it «an act of vandalism», we find out that Badovici thrillingly thanked Le Corbusier for his intervention in a letter: «hats off» – he says – for the murals in E1027» (9).

Your frescoes more luminous and beautiful then ever. Intact. The contented always have

little need to express their joy too vocally… (10)

The problem of authorship rights in architecture is discussed too little and it is hardly regulated, even to this day. It is ironic, though, that Le Corbusier’s intrusive intervention created such a conflict that led to the advertising of the Villa E1027 as a tourist attraction. Without becoming a generator of talk on the issue of authorship in architecture or of the rescue of forgotten master-pieces, E1027 ocasionally seems to be the subject of news like «he vandalized her home when she was away to Tempe à Pailla» – a consequence of reading diagonally. Even more ironic is that this kind of discourse does not come to support the villa or the architect, but it is rather supporting a revolt against Le Corbusier and his being a cad. Moreover, describing some situations that never happened strengthen the mundane aura of the conflict. Against some narratives on this issue, it seems that after 1929, when Badovici started to live in Villa E1027, his alleged relationship with Eileen Gray had already known its end (11). The author of the project never lived here and Corbusier never decided to force himself on the house out of spite, as some articles from the cultural press are hinting.

The house, meanwhile, a fragile-looking thing, endured several forms of violence. Le Corbusier visited and, apparently outraged that a woman could have made such a significant work in a style he considered his own, assaulted it with a series of garish and ugly wall paintings, which he chose to execute completely naked. He would later build a retreat for himself nearby, and drowned in the sea next to E1027 in 1965 (12).

First of all, this kind of attitude shows very precisely why one needs to look at things form the lens of gender studies: the statement above raises the issue of the fragile and defenseless house – a victim «per se» before the unleashed power – before the architect: monumental, male, white, envious. But Eileen Gray never assumed such a stand, on the contrary: she is active in the professional sphere, with her own vision on the moment, queer and without any issues in taking a critical stand towards the men that used to dominate the profession during those years. Eileen Gray and Le Corbusier were not strangers to each other and the latter openly admired the architecture of the villa on many occasions up until the moment of the murals (13) – besides, the two met through Badovici in the ’30s, in an atmosphere of mutual admiration. We have to add that Le Corbusier was a big promoter of his own architecture, not at all retained in this respect, subsequently being very proud of his murals, on top of all the support he had. As Eileen Gray was not self-promoting (her furniture starts to be mass produced in 1970) and was not receiving the same exposure, Le Corbusier’s compliments brought her no benefit – on the contrary, Villa E1027 is sometimes associated with Badovici and, after the murals, even with Le Corbusier (14).

Moreover, Eileen Gray is given very little importance even if in 1994 Caroline Constant places her work in the context of the second half of the 20th century in a very relevant research project on the contribution of the architect. Far from practicing marginal architecture, Gray totally rejects the spirit of modernist architecture which she deems austere and emotionless by investing it with her own interpretation, a personal assembly method of the specific language this architecture uses. Nevertheless, the first online searches for «women in modernism, women in architecture» or the like do not mention her among the relevant figures. All the same, she appears in an article named «10 Most Overlooked Women in Architecture», a whole other story – just as inappropriate as the phrase woman-architect in itself. Architects like Minette de Silva, Jane Drew, Jane Jacobs, Lina Bo Bardi or contemporary figures like Denise Scott Brown or Madelon Vriesendorp recently «retrieved» in the collective memory of the guild are also «overlooked» in the history of architecture, although they are listed (at a first online search) today among the pioneers. A hierarchy showing the extent to which these architects have been forgotten (an attitude attacked by Dorte Mandrup) (15) is only helpful if we want to measure the degree of condescendence contemporaneity is capable of.

Without bringing to the table the necessity of intersectional approaches that have only recently started to slip into the critical view of the professional practice (16), it would probably be necessary to assume an attitude that does not begin with «on a scale from one to ten, about how forgotten have you been in the history of architecture?».

E1027 – The psychoanalytic perspective

Corbusier was an intruder in E1027, the nest where the Gray-Badovici couple used to spend their summers up until when Eileen decided to build her own house in Castellar in 1934 (17). What was Le Corbusier doing here under the circumstances (19)? What was Le Corbusier doing here especially after he writes to Eileen Gray the same year he painted the murals:

I am so happy to tell you how much those few days spent in your house have made me appreciate the rare spirit which dictates all the organization, inside and outside, and gives to the modern furniture — the equipment — such dignified form, so charming, so full of spirit (19).

Was he envious, did he paint the mural in order to appropriate the villa? Was Eileen Gray his Other? Was the E1027 Le Corbusier’s «objet petit»? Or, moreover, by the token of rock stars that destroy the hotel rooms after the tour: did Le Corbusier use his own idea that ‹the role of a mural in architecture is to «destroy» the wall, to dematerialize it› so as to metaphorically tear down Eileen’s walls (20)? «For Le Corbusier, the mural is a weapon against architecture, a bomb» (21) when it is not a means to tell a story (22). And the story Le Corbusier wanted to tell above all at Cap-Martin was the one about the women in Algier (23), with whose portraits he filled a few of his travel notebooks (24). The women from Algier were Le Corbusier’s Other, one that he could not possess but by drawing. (25) He built the refuge, the Cabanon, close by so as to be able to keep E1027 under observation and he committed suicide in front of Eileen Gray’s villa, in the waters of Southern France because he realized that he was never capable of such architecture – or – he did not commit suicide, but his death was ironically witnessed from the hill by the villa protected by vegetation, fragile and perennial (26).

E1027 – The biased perspective

Jean Badovici, Le Corbusier’s friend, the one who dedicated several articles and issues of the magazine «L’Architecture Vivannte», (27) to him at the beginning of the 1920s, had a house at Cap-Martin, villa E1027. The villa had been designed by a close friend, Eileen Gray, (28) the first dwelling signed by the architect after many ample interior design projects. Being very close friends, Le Corbusier and his wife, Yvonne Corbusier, would spend holidays together with Badovici and Madeleine Guisot, his partner, at E1027. At the end of the 30s, Badovici invites Le Corbusier to paint a few walls in the villa. Of course, Le Corbusier’s intervention might be immediately defended, as he himself does, foreseeing the conflict, though the idea that any house has its own life after the architect lays it into the world – an after-life that enriches and spiritually gifts it.

The walls chosen to receive nine large paintings were the most colorless and insignificant. In this way the beautiful walls have remained and the indifferent ones have become interesting….. This villa that I animated with my paintings was very beautiful, white on the interior, and it could have managed without my talents. One must recognize above all that the proprietor and I had witnessed the nourishment and development of a spatial phenomenon – a colored ambiance and spiritual (or lyrical) atmosphere – as, little by little, the paintings emerged under the brush. An immense transformation. A spiritual value introduced throughout (29).

He only bore the guilt of the invited artist, the guilt for the actual artistic act – and after all he pulls the villa out of a kind of obscurity. Moreover, Badovici permitted and encouraged the project. Corbusier was coordinating constructions sites for Rebutato’s – the owner of «Etoile du Mer» bistro – dwellings, where all the team used to have lunch. Le Corbusier’s fairy tale house was not E1027, it was the Cabanon, the little refuge he gifted to Yvonne; he built it right here, at Cap-Martin because here is where he made friends, so he was fond of the place. However, the Cabanon was not Yvonne’s fairy tale house, as she had to sleep with her head in the improvised bathroom, on a foldable bed, because of the narrow space.

E1027 – The romantic perspective

Although there is no correspondence to explicitly attest the love relationship between Eileen Gray and Jean Badovici (30), the two seemingly had a romantically infused friendship, relationship that ended before Badovici moved in the villa E1027 with Medeleine Goisoit – towards who he was mean in Yvonne Corbusier’s opinion (31).

In what concerns his relationship with Eileen Gray, we could believe that it was founded on the professional admiration the editor of «L’Architecture Vivante» for the architect – as well as on some emotional tension to be found in their intellectual relationship, suggested by the only letter he addresses her:

Many Thanks, dear Miss Gray, for your kind words. Enjoy, Miss Gray, the rest you so need [… the pleasure that the Cote d’Azur can offer you… text in roman erased]. It was with the joy of one who is fondly attached to you that I read your reminiscences in your letter. [My admiration and my need to confess and express myself… You cannot escape from yourself by fleeing to others; you have to search deep in your own being to find equilibrium… text in roman erased]. I am flatered… that you have confidence in me, even more so for your kindness in wishing to make your gentle [illegible word]. In any case, I have tried to clothe this passion in the seemliest way possible. And in order to ennoble it have tried to set it alongside all that men hold most respectable (32).

In lack of any other proof, there is nothing to make us believe the two had indeed a romantic relationship. All the same, this connection generated E1027. Even the name of the villa elliptically preserves the story: E1027 – E from Eileen, 10 and 2 – Badovici’s initials in the alphabet, and 7 – the position of the letter G, the initial of Gray – thus she symbolically embraces him (33).

Is it right to suppose that Badovici encourages Le Corbusier in his mural intervention in an attempt to appropriate the villa? Is it right to suppose that, in an egotistic attach Badovici gives up «everything that makes a respectable man» and wears the coat of revenge? Of course, we could suppose all this, but we cannot judge it here, now, in a critical manner.

Bibliography:

• Peter Zumthor, «Atmospheres. Architectural Environments. Surrounding Objects», Birkhäuser, Basel-Boston-Berlin

• Tim Benton, «E-1027 and the Drôle De Guerre.», AA Files, no. 74 (2017), p. 123–43

• Paul Larmour, Irish Arts Review (2002–) 32, no. 1 (2015), p. 131

• Beatriz Colomina, «Battle lines: E.1027», Renaissance and Modern Studies, 39:1, p. 95–195

• Rykwert, Joseph «Eileen Gray: Two Houses and an Interior, 1926–1933», Perspecta, Vol 13/14 (1971), p. 66–73, The MIT Press

• Caroline Constant, «E.1027: The Nonheroic Modernism of Eileen Gray», Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 53, No. 3, (Sep. 1994), p. 265–279, Univeristy of California Press

• Moma, No. 13 (1980), «Eileen Gray», p. 3, Musem of Modern Art

• Dorte Mandrup, «I am not a female architect. I am an architect», Mai 2017, online: https://www.dezeen.com/2017/05/25/dorte-mandrup-opinion-column-gender-women-architecture-female-architect/, date accessed: 5/07/2019

• Alastair Gordon, «Le Corbusier’s Role in the Controversy Over Eileen Gray’s E.1027 Wall Street Journal», August 2013, online: https://www.wsj.com/articles/le-corbusiers-role-in-the-controversy-over-eileens-grays-e1027-1376948447, date accessed: 5/07/2019

• Alastair Liz, «Le Corbusier’s holiday home on France’s Côte d’Azur», The Guardian, Martie 2012, https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2012/mar/02/le-corbusier-home-france-nice, date accessed: 28/06/2019

• Rowan Moore, «Eileen Gray’s E1027: a lost legend of 20th – century architecture is resurrected», in The Guardian, apud. Eileen Gray, online: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/may/02/eileen-gray-e1027-villa-cote-dazur-reopens-lost-legend-le-corbusier , date accessed: 20/07/2019

• Khensani de Klerk, ‹Dead Fish on the Beach: the Problem with «Women in Architecture»› online: https://www.archdaily.com/918877/dead-fish-on-the-beach-the-problem-with-women-in-architecture, date accessed: 29/06/2019

Romană

Romană English

English